|

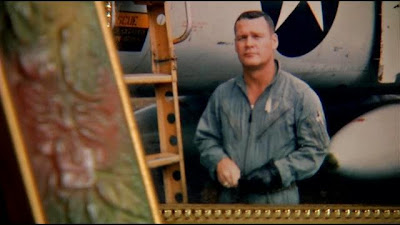

| Col. Charles E. Shelton |

“The art of writing is the art of discovering what you believe.” Gustave

Flaubert

In the early days of

the Vietnam War, Charles Shelton, was shot down over Laos while taking

reconnaissance photographs of Viet Cong and Laotian military POW camps on the

shared border between the two countries.

It was his thirty-third birthday. His plane was armed only with cameras, but his

fighter jet escorts saw his parachute deploy, watched him float to the earth

and land in the steaming jungle, and they talked to him repeatedly over his

radio throughout the night. He spent

three days hiding from Viet Cong and Laotian patrols before being captured and

transported back to one of the very prisons he had been sent to

photograph. Over the next years, he was

tortured and beaten and robbed of his freedom.

In return, he killed three Viet Cong interrogators with a folding chair

while he was locked in chains. He

attempted to escape numerous times. He

refused to be beaten into giving information, to the point that his captors

were so afraid of him that they put him in the ground in a coffin-sized space

with steel bars on top. He was

continuously guarded in this confined space by two soldiers with machine guns

over the span of several years.

Back in the world, his

wife, Marian Shelton, refused to give up the search for her husband. She petitioned congress, the president, and

military leaders. She interviewed men

who escaped or were released from the same prison where she suspected Charles

was held. She requested classified

documents through the Freedom of Information Act. She also continued to raise their five

children alone, never losing faith that her husband would one day return.

Over the years, there

were sightings of him: in other military

prisons, in China, in a number of Viet Cong strongholds. During his captivity, Charles was promoted to

the rank of colonel. He did not appear

when Vietnam exchanged the final POWs in the 1970s, when the official word was

that all prisoners had been returned. One

report Marian received on her husband was that President Richard Nixon and

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger made a deal with the Vietnamese to pay a

ransom for the return of certain high ranking military men still held captive,

including Charles Shelton. When the time

came to pay, Nixon and Kissinger were embarrassed by the fact that the Pentagon

had announced that all U.S. service men had already been returned, either alive

or dead. Because they did not want to

appear to be liars, they reneged on their deal and the Vietnamese sold the

remaining soldiers to China. Marian

still would not give up. She traveled

illegally to Laos and Vietnam to examine for herself the prisons where her

husband was allegedly held captive for all those years. She fought and fought, often in the deepest,

darkest despair, holding out that her husband or his remains would be found.

President Ronald

Reagan mounted a rescue attempt in the 1980s.

Supposedly, the covert operation involved a group of Hmong tribesmen in

the region who managed to find Charles and another well-known prisoner, David

Hrdlicka, and secret them out into the jungle to rendezvous with American

forces. Along the way, an enemy patrol

happened upon the rescue attempt and Charles and Hrdlicka were forced to play

as if they were captives of the Hmong.

The tribe claimed they had found the two soldiers wandering in the

jungle and were returning them to the prison.

The operation failed. In the end,

President Reagan promised Marian that Charles’ case would remain open as a

symbol for all the American soldiers who were lost and never returned during

that awful war.

The last known

sighting of Charles Shelton was in the late 1980s. He would have been at that time more than

twenty years in captivity. Reports from

CIA operatives and other agents in Vietnam and China said he was now a

toothless old man, still being held prisoner, teaching English in China. Marian continued her fight to find her

husband, or to bring home his remains.

Her children grew up. One became

a Jesuit priest, another an actor. In a

strange irony, John Shelton, the actor, played his father in an episode of the

television program Unsolved Mysteries.

In a tragic denouement

to the story, Marian Shelton, in despair over never finding her husband after

three decades of battling with the United States government and the governments

of Vietnam and Laos, went out in her backyard in 1990 and shot herself. She is buried at Arlington National Cemetery,

one of the few civilians given such an honor.

The now adult children decided they had enough of a war that took both

their parents, and asked the American government to declare Charles dead. An empty tomb marked with his name is next to

Marian’s grave at Arlington.

The narrative of us is

constantly disappearing, yet it is also constantly renewed. New stories form as older ones die away. We die twice, once when we physically die, and

a second time when everyone alive who remembers us dies. Few of us will have the immortality of a

Shakespeare. Therefore, human culture

always needs the storytellers, the documentarians, to tell the world the

stories of the past because the past is always telling us what the present

means and what the future might hold.

The language of narrative and the writers of stories are imperative to

the world and human society. A culture

locked in amnesia is a culture destined to die sooner rather than later.

It is exactly because

of these limitations of life—the paradox of human beings: how do we live in a world where we are

destined to die?—that makes writing so important. The wise human being knows the lyrical

melancholy of this life, the impermanence and suffering outlined and accepted as

tenets of human culture within, to cite one example, Buddhism. Job in the Bible is another example of the

human being beset upon by the forces of the world and existence. Like him, we face trials every day. We are challenged every day. We must rise up, like a phoenix from the

ashes of the past to renew and live this new era. We live the cycle of seasons from the moment

we rise in spring to when we lay ourselves down in the fall of the year and

transcend into the dead of winter. All

is cyclical; that is the way of this world.

We must jump in and do what we can, where we are, with what we

have. That is my model as a writer—tell

the best story I can, as truthful and prescient as possible with the tools I am

given.

Why is this need to

tell the story so critical? Ultimately,

telling the story is to invite healing.

Often, the story festers like an infected wound and the storyteller, by

opening it up to the community, drains the wound and cleans it out so that

healing can begin. This is apparent in

the recent wave of shootings of black men by police officers. The community is festering with unrest, with

discrimination, with hatred and bigotry.

Only through story—both sides of the story—told with objectivity and

equality, can the community begin to heal.

Understanding is key because fear of the “other” only breeds hatred and

violence. And the “other” is really

us. We attempt to distance ourselves

with words and categories and racial language, but we are all human.

In the realm of writing

as an art, I am a witness. I bear

witness to injustice and I tell the story.

I bear witness to discrimination, to heartbreak, to the ravages of

disease, to the loneliness of the individual.

I document the pain, suffering and impermanence, not so that it will

end, because it will not, but to help others recognize their own challenges in

the lives of others. I bear witness to

the fact that no person stands alone—we must die alone, but we are in concert

with others who have crossed over before us.

Dying is not unique; we all die, and in that, we seek comfort. This life is not the end, but a stage in a

longer existence stretching over the horizon to infinity. All of us are a part of the Over-soul, the

Atman so revered in Hindu and Buddhist philosophy and adapted in nineteenth

century America by the Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David

Thoreau and Walt Whitman. We carry a

piece of the soul of humanity, all of us interconnected. However, because we all die, because we all

share similar experiences and stories, does not mean we are expendable or lack

uniqueness, or that our stories do not deserve the telling.

All acts are

spiritual. All art is spiritual. The corporeal part—the physical book, the

painting on the wall, the cellist on stage—these are things we can feel (and

read), see and hear. Art appeals to the

five senses, certainly, but it also raises the human spirit. We are reminded by art of the ethereal beauty

of being alive. The Spirit moves through

human beings; it embodies and lives within the artist’s brush, the writer’s

pen, the musician’s notes on the staves.

It is the human being who brings the Spirit out into the world. It is through art and culture, language and experience,

that we transcend our base nature. It is

how we deal with sorrow and joy, the tragedy and exhilaration, of living day to

day.

In the end, there is

no more powerful attraction than the words, “Let me tell you a story…” It is a magical incantation that summons the

ghosts of the past and the dreams not yet realized. It is the story of a family who waits across

the years for a father to return home.

And the story must be told.

|

| The Shelton Family today |