Wednesday, December 21, 2011

Blue Nights*

On a recent Saturday, I attended the funeral of a sixteen year old girl. In the space of a single week, she had been diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor, had surgery, and died. One week to go from being full of life to ashes. As I sat in the cold church watching the service, I realized that her parents had been transposed into an entirely different reality, one that most people could not access, and one that haunts every parent every day: the death of a child. Parents should never have to bury their children.

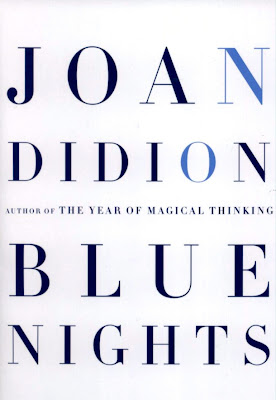

It was a coincidence that at the time of this funeral, I was reading Joan Didion’s Blue Nights (Knopf, 2011), a book that takes as its theme the death of a child, although Didion’s daughter, Quintana, was not a child when she died. For Didion, her death launched an inquisition of self, a clear-eyed, unsparing review of life and parenting, and of course, loss. The book follows Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (Knopf, 2005), a meditation on the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne. The two deaths are deeply entwined; Quintana suffered a series of illnesses and was in the hospital when Dunne dropped dead of a heart attack at his dining room table one evening after visiting his daughter. In a very short period of time, Didion lost two-thirds of her immediate family.

Didion is the rare writer who works in a number of genres. Together with Dunne, she wrote movie scripts including Panic In Needle Park (1971) and Up Close and Personal (1996). Her novels include Run River (1963), Play It As It Lays (1970), and The Last Thing He Wanted (1996). However, it is her nonfiction that stands out, a genre often called New Journalism, but is simply composed of sharp observation and razor-edged nonfiction prose that utilizes the first person. Didion is not a polemicist like Christopher Hitchens, but a writer who conveys the emotional and physical truth of a scene and allows the reader to draw conclusions. She gives us the world through her eyes, and she does not shy away from the dark matters of the human heart, the slippery slope of the center disintegrating beneath us. Her nonfiction books, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), The White Album (1979), and After Henry (1992) contain some of the best essays of the late twentieth century.

In Blue Nights, Didion uses a circular and fragmentary style of prose poetry to examine both Quintana’s life and death as well as her own parenting. Her daughter was adopted, and loved to hear the story of how she came to them: the birth at St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica; the way the hospital would give them no information about the baby’s family; the way John told the story of “Not that baby…that baby. The baby with the ribbon,” as if choosing a beautiful jewel in a store window. For Didion, it was then that the questions started: “What if I fail to take care of this baby? What if this baby fails to thrive, what if this baby fails to love me?” The worst question was almost too much to contemplate: “What if I fail to love this baby?”

Early on, Didion had a foreshadowing of the things to come: “It is horrible to see ones self die without children. Napoleon Bonaparte said that,” she writes. “What greater grief can there be for mortals than to see their children dead. Euripedes said that. When we talk about mortality we are talking about our children. I said that.” She goes on to write that now that her husband and daughter are dead, she fears not death itself, but not dying.

Foreshadowing the end of things, the decay of culture and society, are the threads running through Didion’s work. This from Slouching Towards Bethlehem: “The center was not holding. It was a country of bankruptcy notices and public-auction announcements and commonplace reports of casual killings and misplaced children and abandoned homes and vandals who misplaced even the four-letter words they scrawled. It was a country in which families routinely disappeared, trailing bad checks and repossession papers. Adolescents drifted from city to torn city, sloughing off both the past and the future as snakes shed their skins, children who were never taught and would never now learn the games that had held the society together. People were missing. Children were missing. Parents were missing.” Not far off from today, with our gunman firing indiscriminately into cars in Hollywood, workplace shootings, and mothers who fail to report their children missing, whose children later turn up dead, and for whose murder, they are acquitted. Seventh graders execute each other in classrooms. Joan Didion’s work was never more prescient.

In this book, Didion turns her pen on herself only to discover, there are no easy answers. The blue night of which she speaks is the way the light dies at twilight during early summer in New York, where she now lives. She connects the blue night to “illness, to the end of promise, the dwindling of days, the inevitability of the fading, the dying of the brightness. Blue nights are the opposite of the dying of the brightness, but they are also its warning.” She returns to this motif at the end of the book, writing to Quintana? John? Herself? “Go back into the blue…what is lost is already behind locked doors. The fear is for what is still to be lost. You may see nothing still to be lost. Yet there is no day in her life on which I do not see her.”

This is what I wanted to tell the grieving family. There will never be a day when the pain of loss subsides. There will never be a day when you won’t think of your child. But that is the way we live now, with loss and absence and sorrow, even in spring.

The Buddhists tell us that pain, suffering and loss are part of life, and must be accepted as such. Still humans go on and on, raging against the dying of the light, reaching out to hold on for just one more second, the blue light of memory.

*Writer Annie Wyndham was nice enough to mention this post today (12/22/11) on her blog. Access her piece here.

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Arguably (Updated 12/16/11)*

There is no doubt that the world of arts and letters will be a poorer place without Christopher Hitchens. His latest book, Arguably: Essays by Christopher Hitchens (Twelve, 2011) is another brick in the wall of his substantial oeuvre. Coming in at well over 700 pages, filled with 107 essays, and spanning what appears to be every subject known to humankind, the book works well as a doorstop or tool for blunt force trauma as well as for literary enlightenment. But these are superficial matters. The deeper truth is that Hitchens is a formidable literary critic, an historian, a raconteur, and a social critic bar none.

Hitchens’ work can be found in publications such as Slate, The Atlantic, Foreign Affairs, The New York Times Book Review, and of course, Vanity Fair. In that last magazine, Hitchens is nearly the voice most recognized, and in fact, his writing has served to establish that Vanity Fair style, a kind of intimate storytelling voice that is “in the know.” He seems to have read every book, every journal, indeed every word published in the literary journalism universe. He can write with depth and insight, and often wit, about politics, the military, history, science, philosophy, and literature. He is the very definition of the life of the party.

Arguably is stunning in the sheer breadth of what he has covered over the last decade. Hitchens is most comfortable when writing about the world and not himself. His recently published memoir, Hitch-22 (Twelve, 2010), is an excellent book, but never completely escapes a kind of self-consciousness, and reveals Hitchens’ penchant for name-dropping. In Arguably, Hitchens is at his best, stabbing into the heart of the matters at hand, ripping apart facades and fabrications, and cutting to the bone of literary icons and posers.

His section on history, “All American,” assesses the legacies of literally every significant American from the Revolution forward: Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain, John F. Kennedy, Upton Sinclair, Saul Bellow, John Updike, and his frequent sparring partner, Gore Vidal. Considering that most of the essays are brief, Hitchens dives in and brings us to the sharpest of points with energy and verve. His word pictures are often not pretty. “As president, Jefferson began to suffer intermittently from diarrhea (which he at first cured by what seems the counterintuitive method of hard horseback riding), and though he was unusually hale until his eightieth year, it was diarrhea and a miserable infection of the urinary tract that eventually carried him off.” Historical details that our teachers left out back in school. He speaks of Lincoln’s life long struggle with spelling and pronunciation, and details how the great president’s clothes were often shabby and ill-fitting.

Several figures make recurring appearances throughout the book. Hitchens has long been a fan of George Orwell, and the British writer is a touchstone for him. There is a deep and abiding connection between Orwell the essayist and Hitchens, and in this collection in particular that communion is acute. His interest in communism is also apparent as a through-line in many of the essays, as is his strong feeling that Saddam Hussein had to be removed and that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were justified.

Hitchens makes no excuses for his beliefs, nor does he allow himself to be pigeonholed. Many people have been confounded by his latest forays into neocon territory, but Hitchens does not play favorites. He follows his heart and mind wherever they lead, and he appears to not care a whit whom he offends. Here is a guy who supports the war on terror, but also allowed himself to be water-boarded in an effort to determine if the procedure should be considered torture. It is quite clear from the title of the essay which way he comes down: “Believe Me, It’s Torture.”

In a collection of this magnitude, it is expected that there will be a few missed notes, but for the most part here, Hitchens is true to his contrarian nature, and a joy to read. He challenges us to be better readers, deeper thinkers, more worldly students, and he never panders or condescends. I take that back; he is not kind to idiots and liars, but they deserve what they get. Along the way, jihadists and terrorists also do not fare well. What I found most startling here is Hitchens’ love for his adopted country, America. However, any thoughts that he has mellowed or become sentimental should be left at the door.

Over the entire book hangs the pall of Hitchens’ battle with cancer. “I was informed by a doctor that I might have as little as another year to live,” he writes in the introduction. “In consequence, some of these articles were written with the full consciousness that they might be my very last.” Rest assured that Christopher Hitchens will go to his grave as one of the best social critics of the age, unbent, unapologetic, and razor sharp. Arguably, he is an enlightening voice in a darker age.

*Update 12/16/11: Christopher Hitchens died yesterday. He was 62. Please read this reflection on his life and writing by his good friend and Vanity Fair editor, Graydon Carter.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)