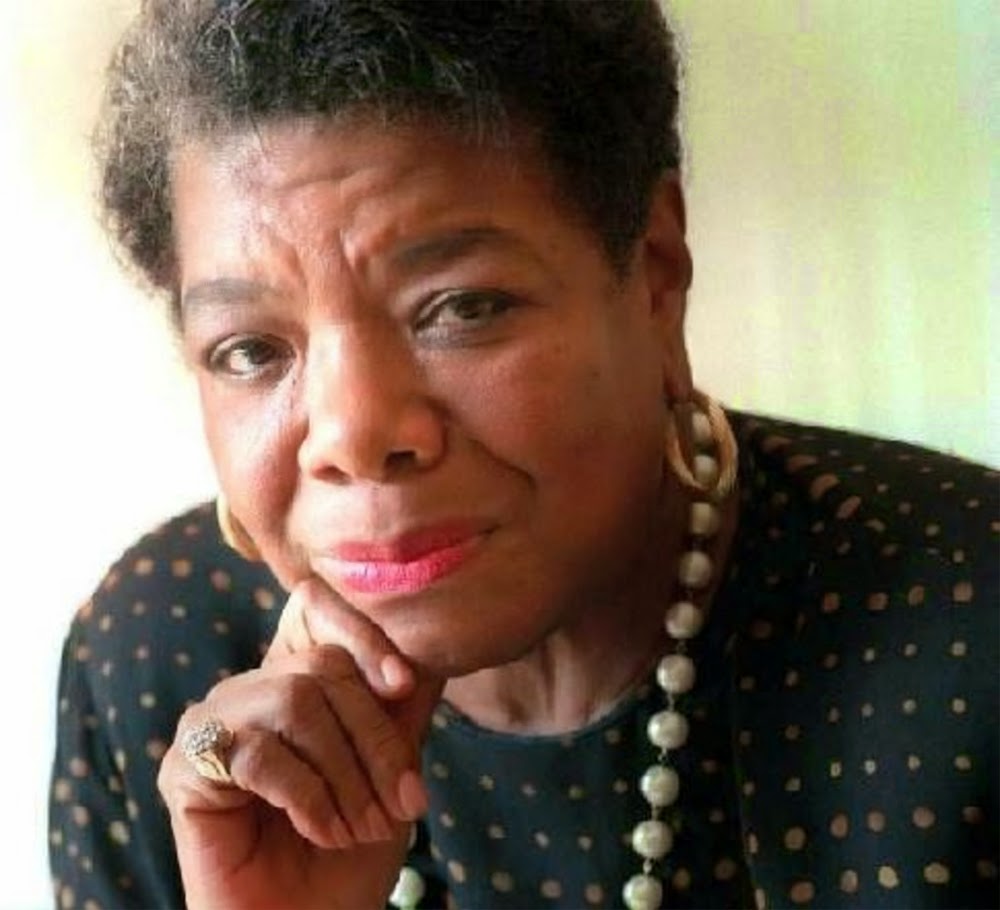

The thing I most appreciate

about celebrated writer, Maya Angelou, is her bravery. She spoke and wrote what was on her mind, never

mincing words. In today’s world of empty

praise and false positive affirmation, this poet is a fresh ocean breeze in the

heat of summer. I love her poetry and I teach

it often along with her memoir, I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings. Her work connects

back to the Harlem Renaissance writers and other African-American artists. The title of her memoir comes from a poem by

Paul Lawrence Dunbar (1872-1906).

However, she is not an artist addressing a particular race; she is a

poet for the ages and for all people, a true American treasure.

The Washington Post published a piece yesterday by Valerie Strauss

that made clear Angelou’s ability to speak the truth. She was exuberant about the election of

President Obama, and he in turn awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom

in 2011. However, she often spoke out

against the president’s education policy known as Race to the Top. She expressed

“concern about the impact of standardized testing” on children. “Race to the Top feels to be more like a

contest,” she has said, “not what did you learn, but how much can you memorize.” Angelou advocated that kids read widely and

deeply, signaling out authors like Tolstoy and Balzac, “because their books

help young people learn about the complexities of the world.” I think her citing of those particular two

authors is interesting, and not common choices in today’s classrooms. I wonder how many students could make it

through Pere Goirot or War and Peace. They would make for ambitious reading.

The Common Core standards

promote reading informational literature over the authors Angelou cites. Many teachers and critics of the standards

say exactly what Angelou says: reading

imaginative literature opens the reader up to the world, to various characters,

to ideas, morals, and values. Angelou

felt it would be shameful for students to forsake poetry for the study of a

business letter or a legal case summary.

Good writing speaks to readers and fosters a world that, while

containing more than enough tragedy and emptiness, also contains great beauty

and wisdom. In the darkness of

oppression and rape, Maya Angelou lost her voice, as she explains in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, but she

recovered and survived, and her story evokes strong emotions for students.

Her words, both in

print and shared in interviews, always contained startling and evocative themes. Listening to her speak meant being prepared

for a surprise, an insight, a way of thinking that remains vital and unique, yet

always clear and piquant. I have typed

out several quotes over the years and pasted them into my journals. Occasionally, one will fall out and remind me

of her power with words:

“If you don't like

something, change it. If you can't change it, change your attitude.”

“We may encounter many

defeats but we must not be defeated.”

“There's a world of

difference between truth and facts. Facts can obscure the truth.”

“What is a fear of

living? It's being preeminently afraid of dying. It is not doing what you came

here to do, out of timidity and spinelessness. The antidote is to take full

responsibility for yourself—for the time you take up and the space you occupy.

If you don't know what you're here to do, then just do some good.”

Maya Angelou died yesterday

at the age of 86. I’ll end with a stanza

from the poem she read at Bill Clinton’s inauguration, January 1993:

“Across the wall of the world,

A River sings a beautiful song,

Come rest here by my side…”