Wednesday, November 23, 2011

American Teacher Fights To Survive

Competing for space in the American mind, which Allan Bloom famously declared closed more than twenty years ago, we have unemployment, a recessed economy, two wars, and a confederacy of dunces vying to be the next leader of the self-proclaimed “greatest country on earth.” Somewhere in the middle of that pack is American education. Every yahoo running for political office from dog catcher to president wants to be known as the education candidate. Yet once in office, those same politicians offer the old tired mantras of standardized test scores and teacher accountability. We must return America’s students to the top of the heap in math and science, they bray. Let’s hope they can read, too.

We have been treated to a number of documentaries in the local cinema over the last few years regarding our education problems in America. There was the much ballyhooed Waiting For “Superman,” (2010) by the people who brought us global warming and the Al Gore PowerPoint lecture; there were also a number of lesser known films like The Lottery (2010) and Teached (2011). Vanessa Roth and Brian McGinn have been flogging their take on the education crisis with American Teacher (2011).

The film follows the lives of several teachers as they navigate the emotional and difficult waters of a typical school year. To be fair, Roth and McGinn are not breaking new ground. The film, The First Year (2001), which aired on PBS, did a much better job of packing the emotional wallop of the daily life of an educator. That film was directed by Davis Guggenheim, who went on to do An Inconvenient Truth (2006) and Waiting For “Superman.”

American Teacher was inspired by the Daniel Moulthrop, Ninive Clements Calegari, and Dave Eggers’ book, Teachers Have It Easy: The Big Sacrifices and Small Salaries of America’s Teachers (New Press, 2005). Eggers went on to help produce the film. Look, one would have had to be living under a rock for the last few years not to know that teachers are the republic’s version of the sacrificial lambs. They work for little pay, even less respect, and in dire circumstances to educate our children. We pay the big salaries to our corporate CEOs and professional athletes while our teachers put in eighty hour weeks and work part time at Home Depot. So the film tells us a story we already know and for which we can easily predict the outcome. However, the portions of American Teacher featuring Jamie Fidler and Erik Benner are exceptionally moving.

Fidler begins the film very pregnant while attempting to teach her class. She purchases her own supplies, and works endless hours for her students. She looks haggard and worn, and one has to wonder if her exhaustive preparation and teaching will harm her baby. Once she returns from giving birth, a miraculously short few weeks, we see her wandering the halls looking for an empty classroom or office in which to pump her breast milk. Other scenes show her spending her limited lunch break on the phone with her medical insurance carrier, determining the procedure for her upcoming pregnancy leave. But she is a diehard teacher through and through, a woman who is fiery and passionate about her work.

Benner works his time in a Texas classroom, while simultaneously coaching school teams and working evenings and weekends at the local Circuit City. He is a bear of a man, appearing to have fathomless reserves of energy. Then, his job at the electronics store is cut, and he moves to a tile and flooring emporium. His days are long and draining, and his hard work forces him to pay a price: the loss of his family. His marriage crumbles and he agonizes over whether to take on extra shifts or spend the time with his children.

Director Brian McGinn says that the film purposely avoids politics, or assailing any one party, such as teachers’ unions. This film does not participate in the same dust-up instigated by films like Waiting For “Superman.” They did not interview union leaders or charter school entrepreneurs. Education secretary Arne Duncan sneers his way through a comment on teachers, and Bill Gates performs his rumpled version of Steve Jobs on stage talking to an audience, but that’s it. Gates contributed some money to this production, says McGinn, but only at the end when the film was finished. He did not know if Gates had even watched it.

I wonder how many Americans will sit through another documentary about teaching. This country loves the feel-good stories, the films like Stand and Deliver (1988), Dangerous Minds (1995), and even To Sir With Love (1967), none of which were documentaries, but were purported to be based on true stories. The story of education, and its failure in America, defies the classic cinematic narrative. The audience wants the white hats and black hats, the cowboys and Indians. When the house lights come up, there must be a catharsis, and an upbeat ending. We want to know that we are on the right track, and that there’s a workable solution around the next bend. We do not like stories that are downers, and this is why so many films and television shows get the drama of the classroom wrong.

In American education, the happy ending is proving quite illusive. There are no easy solutions, no quick fixes. There’s graft and waste and mismanagement. There are slimy politicians and shady characters waiting to make a fast buck in the rush to privatize our schools. Meanwhile, the kids languish and suffer, and we fall down as a nation.

The film makes a big deal out of other countries who have better education systems. Although they fail to give much detail about what exactly they are doing that works, it seems like the best solution might be to copy what those nations are doing, and build on that. Instead, we get the almost lemming-like focus on standardized test scores, with the resulting cheating scandals when teachers teach to the test because they are always aware of the loaded gun pointed at their heads. Teachers in America kill themselves, buy their own supplies, work outrageous numbers of hours, forego family life, and in the end, find their jobs eliminated in the latest budget bloodbath.

We do not need another documentary to tell us how bad things are. We know: the system is rigged, the fix is in, and nothing ever changes. More and more, bright, compelling, excellent teachers find other careers that offer not only a decent salary, but a chance to work more than five years without a nervous breakdown. Americans do not really want to know the true story of education, because that one isn’t going to end well, and with everything else that is going wrong, we can’t stomach all that darkness.

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Here There Are Only Ghosts

For many of us, “Childhood is the kingdom where nobody dies. Nobody that matters, that is,” as Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote in 1937. It is in our sepia-toned memories of childhood that our futures are born. Never is this nostalgia for our remembrances of things past more evident than in our literature of reflection, the coming-of-age story so prevalent in our life of letters.

Giuseppe Tornatore, writer-director of the Italian film Cinema Paradiso (Miramax Films Presents, 1988; Miramax Classics, 2004), explores his remembrances of his post-war childhood through the experiences of Salvatore “Toto” Di Vita, a fictional, well-known movie director who is forced to re-examine his life’s journey upon the death of his mentor, Alfredo.

“Tornatore pays homage to the American, Italian, and European films that influenced him as a child and as a director,” Stanislao G. Pugliese writes in The American Historical Review. The film had a troubled, but ultimately successful history. The first cut was 185 minutes, and when shown “in 1988 at a small European festival…received a mixed response along with an ambiguous award for ‘best artistic contribution to the first part of a film,’” says Stephen Holden in The New York Times. Tornatore continued to work on the film, trimming it down to 150 minutes for general release in Italy. The cut did not do well at the box office. Returning to the editing bay, Tornatore cut it down to two hours in a last ditch effort to find an audience.

Holden quotes Tornatore: “This was the autobiographical film I had waited my whole life to make, and it felt like the failure of my life.” However, the two hour version was greeted with acclaim. “The shorter version proved a surprise hit at the 1989 Cannes International Film Festival,” Holden writes, “where it won the special jury prize. Cinema Paradiso went on to win the Golden Globe and the Academy Award for best foreign film.”

However, Tornatore was to have his director’s cut after all. He released an extended cut of his film in theaters in 2002. According to Bill Desowitz in the Los Angeles Times, “It’s like watching another movie. We get a sense of closure, and the story takes on greater depth and complexity. The disparity between movies and life becomes more ironic, and the great friendship between the young boy and Alfredo (Philippe Noiret), the local film projectionist who serves as his father figure is much darker.”

The shorter version plays to nostalgia. It is a whimsical film, full of the magic of cinema, and the humor and subtle irony of real life. However, the 2002 film is indeed richer, darker, and even more realistic. To examine this film as literature, as history, as a reflection of changing values, of developing technology, of culture itself, we must look closely at Tornatore’s cut of 2002.

Tornatore’s cut differs from the two hour version by adding about 48 minutes to the end of the film. Up until that point, the versions are basically the same.

The film opens with a long pull back shot of a flower pot on a sunny veranda overlooking the sea. Tornatore, throughout the film, makes good use of his location and the bright Mediterranean sun. He shot the film on location in his hometown of Bagheria, Sicily, (Giancaldo is the fictional town in the film), and also in Cefalu on the Tyrrhenian Sea.

As the shot pulls back, we see an elderly woman on the phone. She is looking for her son, Salvatore Di Vita. She has an urgent message for him, but she fails to locate him. Her daughter, sitting across the table from her, tells her to give up her search, but she knows her son would want to hear her message, so she persists.

The film cuts to a man driving through Roman streets at night. In his apartment, we see the weariness in his walk, and in his bedroom, the woman in his bed tells him his mother has called. Someone named Alfredo has died. The man is Salvatore Di Vita, and he lies awake thinking, and the film shifts into flashback.

We see life in a small Sicilian town, post-World War II. The Catholic Church is the supreme rule, even more powerful than the government. Salvatore is nicknamed Toto as a child, a small boy serving Mass in an ancient church. After the service, the priest goes to the town’s one movie theater, Cinema Paradiso, to preview the flicks that will be shown that week. Observed by Toto, the priest rings a bell during each intimate kissing scene, informing the projectionist of what he finds objectionable and what therefore must be edited out before the public sees the movie. This is our introduction to Alfredo, the projectionist, and his relationship with Toto. Alfredo is a middle-aged man with little education. He has become a father, or even grandfather figure to little Toto.

Tornatore does not delve too deeply into the historical background of the time period. He effectively alludes to the historical context. We see water rationing and a street vendor selling nylons, which could only be had at a premium after the war. Toto’s father has not returned from the front lines in Russia, and we are led to believe he is probably dead. This is later confirmed for us in a heartbreaking scene where Toto and his mother are informed of his death and walk home through the rubble of the bombed out town, passing movie posters for the Italian-dubbed version of Gone With The Wind.

Actually, the films we see playing at Cinema Paradiso serve to establish the timeline of the piece. “In recycling fragments of favorite movies, including Jean Renoir’s Lower Depths [Films Albatros, 1936], Luchino Visconti’s Terra Trema [Universalia Film, 1948], Fritz Lang’s Fury [MGM, 1936], and John Ford’s Stagecoach [United Artists, 1939], Mr. Tornatore treats them as beacons of enlightenment to a benighted culture riddled with fear and superstition,” says Holden.

Tornatore perfectly illustrates issues of class and economics in the film. The Bourgeois intellectuals sit in the balcony of the theater above the peasants, and one takes great pleasure in spitting on the rabble below. And from that rabble, we see something akin to Shakespeare’s groundlings. Some are illiterate. They fight, fall asleep, roar epithets at the screen, throw things (including a feces-laden diaper at the spitter), mimic the actions they see, speak the lines of their favorite films, have sex both intimate and illicit, and of course, laugh and cry all while the dream-life of celluloid plays on the big screen in front of them.

Out in the town square, we see a socialist denied a chance at work—“Go ask Stalin for a job,” he is told. When Toto’s friend, Peppino, leaves for Germany with his family, some kids refuse to say goodbye to him because his family is communist. A mentally ill man roams around screaming at people and claiming the square is his property. The Neapolitan Ciccio wins the football lottery, and a citizen remarks that “It’s always the northerners who are lucky!”

Old women wash tables. Children have their heads shaved because they “have a lice factory up there.” Then they are hosed down with bitter insecticide to finish off any remaining nits.

The centerpiece of this story, however, is the relationship between Alfredo and Toto. In the beginning, it is a tug-of-war: Toto wants to be in the projection booth, but Alfredo wants to keep him out. He bugs the older man for the kissing clips that Alfredo must remove. Alfredo promises him he can have them one day, but for now, they must remain in the booth. So the boy steals pieces of film to play with at home, reenacting scenes verbatim while holding them up to the lamp light. These are his movies, his way of playing and make-believe. When the highly flammable film accidentally catches fire—it was made of nitrocellulose up until the mid-twentieth century—Toto’s hobby nearly costs his sister her life. For that, and his almost unhealthy obsession with movies, Toto is banned from the projection booth and Alfredo is admonished for allowing the boy the freedom to steal film.

The punitive sentence does not last long. Toto schemes to get back into the booth, and good thing, too, as the small boy saves Alfredo’s life when the projector catches fire and the theater burns down. Ciccio with his lottery wealth returns to rebuild the movie house, ending the era of Church censorship and control.

Post-fire, Toto runs the booth himself until Alfredo returns, blind and scarred. He encourages his protégé to stay in school, knowing from experience that a lack of education traps one in places like Giancaldo. Alfredo is the classic character ignorant of book learning, but rich in the wisdom of life and experience. “Now that I lost my sight,” he tells Toto, “I see better.”

As time passes, Toto becomes a teenager, and Cinema Paradiso takes on a more mature, titillating atmosphere. Ciccio books racier and more violent films. A prostitute operates openly in a closet, and Toto samples her wares. The manager catches boys masturbating to the nudity in a film, and Alfredo reveals that when his first wife died, no one told him until he was done with his shift so the evening’s showings would not be interrupted. A small time gangster is murdered in his seat. This is a gritty movie house, not nearly as magical as Toto’s childhood Cinema Paradiso.

Technology also advances. A new type of film doesn’t burn, and Alfredo laments that “Progress always comes too late.” He continues to offer Toto wisdom and advice, especially after he meets Elena. While watching some film footage Toto, himself, shot, Alfredo has him describe Elena to him. “Ah, the blue-eyed ones are the worst,” the older man tells the lovesick teenager.

Toto’s relationship with Elena develops slowly. She comes from a wealthy family, and they do not take kindly to their daughter dating a poor projectionist from a single-parent family. Again, we are reminded of class struggles in post-war Italy. Even as the 1950s progress, we see reflected in the life of Giancaldo the struggle to recover and rebuild. Cars and buses travel through the town square with herds of sheep. The old ways and the new do not meld easily.

In a particularly moving and poignant scene, Alfredo and Toto sit in a doorway. As the camera slowly moves in, Alfredo passionately relates the story of the soldier who falls in love with a princess. To prove his love, the soldier agrees to wait outside her window for a hundred nights. The weather beats him down, “birds shat on him,” and by the ninety-ninth night, “He didn’t even have the strength to sleep.” The soldier abandons his vigil on the final evening, never to return, and letting go of his princess forever. When Toto asks what this story means, Alfredo says he has no idea. The power of the story, the poetry with which Alfredo tells it, and Tornatore’s deft camera work, enhance the scene with cinematic brilliance. The comic payoff is that neither knows what the story means.

Toto is so impressed with the story that he emulates it outside Elena’s window. Elena has told him she does not love him, so he decides to prove his love for her in hopes of winning her heart. It is sentimental and romantic, and Tornatore revels in it. Toto ends his one hundred day vigil at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve. There are fireworks in the sky, and the citizens of Giancaldo throw plates and dishes out of their windows to crash in the streets. Out with the old, in with the new. Alas, but Elena never appears. Later, at Cinema Paradiso, she comes to Toto, kisses him, and swears her love in an emotionally cinematic embrace. The projector spins in the background as Toto and Elena twirl together. This is the marriage of cinema and life, two worlds existing in the same space in the projection booth. One is only a projection of reality, a fiction, while the two lovers are real, and although this would make for the perfect fade out at the end of a movie, in real life, things do not always work out this way.

The lovers’ relationship continues to face obstacles. At the theater, television arrives, and Ciccio invests in a receiver to show the broadcasts on the big screen. Alfredo expresses his disgust with game show programming. During the summer heat, Toto shows films outdoors in a seaside amphitheater, and the cinema continues as the prominent medium of mass entertainment and culture.

Toto and Elena are eventually separated when he is drafted and she is sent off to school. In a last ditch effort to see her before they both leave, Toto abandons the projection booth, leaving Alfredo in charge, while he goes to search for Elena. He promises to return before the end of the film, since Alfredo cannot see to change reels. However, Toto fails in his quest, and when he returns, Alfredo tells him it is better. He must follow his destiny and not hold back for a girl whose parents do not want the relationship to continue.

The largest leap forward for Giancaldo comes while Toto is serving in the military. Upon his return, someone new is working the projection booth. The town is drier, more deserted and desolate, more bleak and small, especially for Toto. And Elena has disappeared. All of his letters are returned, and he has no way of locating her. Alfredo has become a recluse, rarely venturing out from his stifling rooms. Toto goes to see him and asks why he does not speak much anymore, or get out more often. “Sooner or later,” the old man tells him, “a time comes when it’s all the same, whether you talk or not.”

He takes his elderly mentor down to the seaside, and there, in a field of twisted ships’ anchors, Alfredo tells him he must flee Giancaldo. The land is cursed, he says, and there’s nothing left for Toto there. “The thread is broken,” Alfredo sighs. Everything has changed. When Toto asks what actor said that in what movie, Alfredo tells him nobody said it. They are Alfredo’s words. “Life isn’t like in the movies,” he says. “Life is much harder.” With intensity, the blind man leans toward Toto. “I don’t want to hear you talk anymore. I want to hear others talking about you.”

Tornatore cuts back to the present of the film with Salvatore sitting up in the dark of his bedroom, remembering. He cannot sleep because he is lost in the past. He jump cuts back to the train station in Giancaldo as young Toto leaves. Alfredo tells him not to come back, and as he pulls him close in an embrace, whispers, “Whatever you end up doing, love it, the way you loved the projection booth at Cinema Paradiso.”

This action leads to an airplane landing on Sicily. Toto, Mr. Salvatore Di Vita, has come home for Alfredo’s funeral. True to his mentor’s wishes, he has not been back for thirty years. His elderly mother greets him, and he finds his bedroom preserved like a museum. His mother tells him she remodeled the house with the money he sent her.

In his old room, Tornatore sweeps his camera lens over the pictures on the wall, accompanied by Ennio Morricone’s lyrically sad score. There is the lost father, Toto’s first Holy Communion, and finally, the child Toto with Alfredo. The camera lingers before we cut back to see Salvatore’s eyes welling with tears.

At the funeral, Salvatore sees all the old faces from Cinema Paradiso, out to pay their last respects to the projectionist. They are grey and weathered by time. They pass the theater, now closed and dilapidated, about to be torn down to build a parking lot. Nobody goes to the theater anymore, a wizened Ciccio tells him. “The old movie business is just a memory.” The rise of technology killed Cinema Paradiso—television, videos, et cetera.

Later, in an eerie, haunting moment, Salvatore goes inside the shuttered theater. As he walks through the destroyed interior, he hears the cheers of the audiences of the past, the echoes of history through the dusty curtain of memory. Jacques Perrin’s acting is superb here. With simple expressions, no dialogue, and Morricone’s melancholy score, he conveys every heartache his character experiences in his walk through the abandon movie house.

From here, Tornatore’s additional 48 minutes come into play, and the differences between the 120 minute and the 174 minute versions are clear. In the shorter version, Elena never appears again and is a wistful memory for Salvatore. Cinema Paradiso is demolished and the famous director returns to his life in Rome.

In the 2002, 174 minute film, Salvatore sees a girl on the street who appears to be Elena as he remembers her. He follows her, and wonders if she is somehow connected to Elena. Back at his mother’s house, he watches his films of Elena taken back when he was a younger man. It is clear she was, and is, the love of his life, a colossal missed opportunity that has haunted him now into middle age.

He sits at the dining room table to have a talk with his mother. He apologizes for not having come home sooner. She tells him she understands that he had to go away. “Here there are only ghosts,” she says with glistening eyes. Then she drops a bombshell—when she calls him, she knows none of the women who answer truly love him. She wishes he was settled, in love, happy.

Salvatore continues to follow the girl and discovers she is Elena’s daughter. His former love is now married to one of Salvatore’s school friends. He calls her and they meet up in the field of anchors where Alfredo told him to leave Giancaldo. There, in Elena’s car, Salvatore tells her of his lifetime love of her. She tells him that she came to Cinema Paradiso that day to say goodbye, but Alfredo told her that he, Salvatore, did not want to see her anymore. Dejected, she left a note for him, but since he never got in touch with her, she had no choice but to go on with her life. Alfredo, he realizes, may have thwarted his happiness for the good of his future. According to Bill Desowitz “Alfredo seems to betray Toto since it is he who pulls the strings of the young man’s life to the point of making him sacrifice the great love of his life on the altar of another love, that for the cinema.” This renders the Alfredo-Toto relationship in much darker tones. The story shifts from sentimentality, comedy, and nostalgia, to bittersweet nostalgic postmodernism.

The reunion scene ends with a tryst. Tornatore backs his camera off, and we see the car in the distance, illuminated by the spot lights from the sea coast, and we hear the crashing of waves. As Elena makes clear in subsequent scenes, this long-delayed union of these two characters is a one-time thing. Cinema Paradiso, like the possibility of their lives together, is demolished, and Salvatore returns to Rome.

Giuseppe Tornatore maintains his famous conclusion in both versions. Alfredo has left a reel of film for him. Back in his screening room in Rome, Salvatore has the film cued up, and sits in the empty theater to watch. What follows is a montage of all the intimate scenes of lovers kissing that Alfredo had to remove from the movies by order of the Church. It is a beautiful denouement, cutting back and forth from the action on the screen to Salvatore’s face. Once again, Jacques Perrin’s expressions and Morricone’s score create magic. The scene distills the power of cinema to move us and reveal the scope of human emotion. It is a sad, brilliant, bittersweet moment worthy of its place in the pantheon of exquisite cinematic moments.

When analyzing film, we find three levels of quality: flicks, movies, and films. Flicks are lighthearted, explosion-and-car chase extravaganzas, or horror pictures; movies might be character-driven, romantic comedies. Films are serious works akin to literature, and therefore can be analyzed with a critical eye like good novels or poetry. Cinema Paradiso is most decidedly a film, especially Tornatore’s director’s cut.

There are several key aspects of the film that we can examine using literary terms and ideas. Tornatore is a master of literary symbolism in film. His central character is Salvatore Di Vita—“salvation of life” in translation—his doppelganger who shares Tornatore’s love of film. He begins with Salvatore transitioning to memory after learning of Alfredo’s death. The journey into the past is symbolized and initiated by wind chimes hanging outside his bedroom window. Tornatore imposes the shadow of the chimes, gently buffeted in the breeze, across the actor’s face even as their melodic tinkling can be heard.

The Catholic Church plays a key role in the life of Giancaldo as the moral and instructive force in daily events. Tornatore uses the icons and statuary of the religion to reinforce the presence of the Church in every day life. We see a Sacred Heart statue in a priest’s closet, and when Cinema Paradiso burns, Tornatore gives us a tight shot of the Virgin Mary surrounded and consumed by flames. The fire ends the Church’s influence on the theater and lessens its control of the town. The priest no longer censors the movies scheduled to play there, and Ciccio brings in racier and more erotic films when the theater reopens.

In the summer scene where Toto as a young man projects films outside in the amphitheater, he is lovesick for Elena. He can see nothing else in his life. “Will this summer never end?” he sighs. The film he is showing is the story of The Odyssey. The scene is Ulysses’ battle with the one-eyed Cyclopes, who, like Toto, can only see the world one way and suffers for this lack of vision.

The piece de resistance of symbolism in the film is the anchor scene where Alfredo tells Toto he must leave Giancaldo. The ships’ anchors take the shape of crucifixes. This small town, provincial life will keep Toto from achieving his dreams, and if he stays there, he will sacrifice his future for others, much as Christ did on the cross. It is ironic and symbolic that Alfredo tells Toto he must flee Giancaldo and never look back amid a field of anchors used to moor ships in the harbor.

In the same way, when famous movie director Salvatore returns home for Alfredo’s funeral, his mother rushes to the gate to greet him. She drops her knitting, but a thread catches on her clothing. Tornatore gives us a tight shot of the cloth unraveling as she hurries downstairs to greet her son. Our lives are often unraveled by our past. This also plays into Alfredo’s earlier admonishment to his protégé that he must leave Giancaldo because the “thread is broken.” However, the image of the unraveling cloth tells us that we can never entirely break free of the past.

Tornatore also uses themes to deepen the resonance of his work. Love, of course, is most prominent. Unlike other more religious views of paradise, Cinema Paradiso is a paradise of imagination, of dreams and schemes played in celluloid on a forty foot screen. Meanwhile, all strata of human life are on display on the floor, the balcony, in the projection booth, and in the vice-laden nooks and crannies of the theater foyer. The theater is all of human life, brimming over with the stench and beauty, the familial and erotic, the lonely sadness and communal joy of being alive.

Religion, specifically the Catholic Church, is a thread that runs through the story. Bert Cardullo, writing in The Hudson Review, says “To be sure, the Catholic Church is still a force to be reckoned with in Giancaldo—we see the villagers at confession, at Mass, and at funerals, and Toto, himself is an altar boy to the vigilant Father Adelfio—but the Church must be content to attract believers with the promise of salvation in the hereafter, whereas the cinema can lure them with the guarantee of salvation from the here and now.” Cardullo sees the movie house and the Church as “two faiths” that “manage to exist side by side.”

In the face of Jacques Perrin, we see the theme of regret clearly in play. It is in this theme that we find the film’s “richly textured realism,” as Rita Kempley notes in The Washington Post. In the character of Salvatore, we are made aware of the sacrifice one makes to achieve his dreams. Often, this regret is a barrier to total happiness and satisfaction in life. “Toto had to give up something in order to get something,” Cardullo writes, “had to give up the community of tiny Giancaldo for the individual achievement of a career in the wide world, and had to leave the village, paradoxically, in order to discover the extent of its benign influence on him.” It is debatable whether one can go home again. Tornatore posits that we can, but we will find neither the place nor ourselves the same.

The biggest regrets come in Salvatore’s feelings for Elena. Their separation, although necessary to his success in the future, was not of his own choosing. There is a point in life when missed opportunities transition into fate—things necessary to our advancement into the future. Salvatore had to let go of Elena to seize his destiny. Yet in the last 48 minutes of the film, we see the price of this separation. That is what makes the director’s cut a better film than the earlier, shorter version.

Lawrence Kasdan, in his film, Grand Canyon (20th Century Fox, 1991), writes that “All of life’s riddles are answered in the movies.” Indeed, even the most exotic of science fiction films tells us about ourselves. When it is done well, film tells us what it means to be alive and what the purpose is of our existence. Cinema brings us to the altar of sorrow and joy, loneliness and communion, bitter vitriol and love. Sitting in the dark, staring up at the screen, we witness the scope and heft of our lives. This is who we are, lest we ever forget where we’ve been, or what we have dreamed for ourselves.

Cardullo concludes that “Cinema Paradiso, then, is a paean to the cinema at the same time that it is an elegy for the cinema, a bittersweet film whose bittersweetness is underscored by Ennio Morricone’s music, which neatly combines the pensive with the buoyant, and Blasco Giurato’s cinematography.” Let us not forget the brilliant writing and direction of Giuseppe Tornatore. This is his film and his parallel universe, and his work ultimately leaves us glowing in the warmth of human experience.

Film can be a reference to history, a pageant dedicated to the spirit of humanity and the human condition. Film can be literature and a window on a culture. Cinema Paradiso is all these things and more.

So, after Alfredo is gone, and the substance of memory has turned to dust, Cinema Paradiso, like all films, must end. The screen fades and the house lights come up. We are startled out of our reverie. Off we go, into the harsh light of our lives, leaving behind the ghosts and landscapes of a parallel universe, the tender kisses of lovers, and the rustling leaves of regret. We are gently reminded that, like all movies, we, too, end. And so it goes.

"Saint Cinema" by Bert Cardullo, The Hudson Review (Autumn, 1990).

“Movies: A Deeper Vision of ‘Paradiso’” by Bill Desowitz, Los Angeles Times 13 June 2002.

"A New ‘Cut’ Only Deepens The Nostalgia" by Stephen Holden, The New York Times 09 June 2002.

"Cinema Paradiso" by Rita Kempley, Washington Post 16 Feb. 1990.

"Untitled" by Stanislao G. Pugliese, The American Historical Review (April, 2001).

Saturday, November 5, 2011

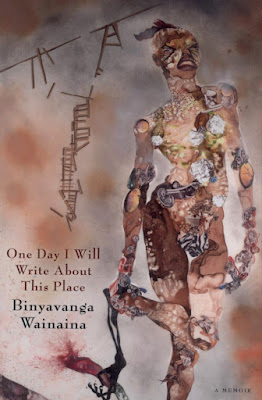

One Day I Will Write About This Place

It is always interesting to pick up literature originating in another culture and find echoes of our own. In that spirit, I was intrigued by Binyavanga Wainaina’s coming-of-age memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place (Graywolf Press, 2011), set on another continent and within a completely different culture.

Wainaina writes about growing up in Kenya, the tensions among tribes and factions, his own mental breakdowns and inadequacies, and finally, his triumph upon finding his path in life centered on the twin suns of writing and literature. Even in his darkest moments, it is reading that saves him, and writing that allows him to capture the fertile decadence of his African life. Wainaina writes how he loses himself in literature, devouring books like a man steeped in hunger. This rabid reading habit comes at the expense of his social life and education. “I do not concentrate in class,” he says, “but I read everything I can touch.”

The echoes of American cultural influence come in the form of television. He cites cultural icons like the 1970s TV series, The Six Million Dollar Man, starring Lee Majors, reciting the show’s distinctive opening narration: “Steve. Austin. A me-aan brrely alive,” he writes in dialect. “Gennlemen, we can rebuild him. We have the tek-nalagee. We can build the world’s frrrrst bi-anic man.”

His experiences in Kenyan schools also echo American institutions. There are the tests that act as gateways to universities and higher education. There are the expectations of his parents that he will choose something lucrative, and their pressure on him to do something with his life. He struggles to find his own path.

In the first two-thirds of the book, Wainaina adopts a highly poetic, fragmentary style of writing. He mixes up descriptive words and sensory perceptions, making for some stunning prose. He speaks of his mother’s voice “like shards of water and streams of glass.” Examples of sound description include, “One bee does not sound like a swarm of bees. The world is divided into the sounds of onethings and the sounds of manythings. Water from the showerhead streaming onto a shampooed head is manything splinters of falling glass, ting ting ting.” He uses creative juxtapositions of adjectives and modifiers as well as interesting combinations and spellings of words.

His poetry is beautiful and effective especially when he writes of his reading life. He closes his eyes to the hot African sun, only to open them a few seconds later and return to his reading. “If I turn back to my book,” he writes, “the letters jumble for a moment, then they disappear into my head, and word-made flamingos are talking and wearing high heels, and I can run barefoot across China, and no beast can suck me in, for I can run and jump farther than they can.”

His language is mesmerizing, intricate, crystalline, simply beautiful. “Science is smaller than music, than the patterns of the body; the large confident world of sound and body gathers. If my mind and body are quickening, lagging behind is a rising anxiety of words.” He captures the rituals of the Catholic Church, which he says are “all about having to kneel and stand when everybody else kneels and stands, and crossing and singing with eyebrows up to show earnestness before God, and open-mouthed dignity to receive the bread.” By far the best line is the one where he assesses his fear of ending up as a school teacher, something he calls “A fate worse than country music.”

Occasionally, the language can be overdone, too obscure and obtuse for its own good. An example: “The sun is the deep yellow of a free-range egg, on the verge of bleeding its yolk all over the sky.” An egg does not “free-range,” only the hen laying it. I am not sure a supermarket egg might not be able to bleed the sky yellow just as competently.

Wainaina does not shy away from his more difficult moments: his breakdowns where he withdraws from everything, including his family, to hide away and read books, avoiding responsibilities or facing his own failures. These difficulties lead to statements of startling wisdom. “If there is a miracle in the idea of life,” he writes, “it is this: that we are able to exist for a time, in defiance of chaos.” He manages to get a handle on his “chaos” and emerge as a writer and journalist.

In the last third of the book, he shifts to a more concrete language as he struggles to write and publish. Noticeably, the tension increases. He realizes the purpose of his journey. “It often feels like an unbearable privilege—to write. I make a living from simply taking all those wonderful and horrible patterns in my past and making them new and strong. I know people better. Sometimes I want to stop writing because I can’t bear the idea that it may one day go away. Sometimes I feel I would rather stop, before it owns me completely. But I can’t stop.” The emotional peak comes when he returns to life and embraces family and country, no longer afraid of the dichotomy. It is then that he decides that “One day I will write about this place.”

The book is by turns moving, poetic, full of grace, tinged by anger and humor. Like the African art that adorns the cover, the book revels in the color, the bloodshed, the tribal conflicts that are so much a part of Africa today. Out of the heat and dust, we are indelibly marked by Binyavanga Wainaina’s poetic prose. His words are infinitely earthy, primordial, ethnic. Yet, his book is filled with a tragic, desperate beauty. His story is that of a young man developing a life of the mind while never truly escaping home.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)